In the Lord’s Army?

There's a song that I grew up singing in Sunday School called I'm in the Lord’s Army . The words go:

I'm too young to march in the Infantry, Ride in the cavalry, Shoot the artillery. I'm too young to zoom o'er the enemy, But I'm in the Lord's Army. I'm in the Lord's Army (yes, sir!) I'm in the Lord's Army (yes, sir!)

There are other variations of the words, such as replacing “I'm to young to march” with “I may never march.” My brothers and I liked it because it had hand motions (which we always greatly exaggerated) of marching, riding, zooming, and saluting. I recently heard it sung in church, and it started to wonder how a song filled with such militaristic language became such a popular children's song. There are many other old hymns and songs that talk about the army of the Lord, such as Onward, Christian Soldiers and Keep on the Firing Line , but this song seemed different to me. Instead of focusing on a strictly spiritual battle, it talks about both spiritual and physical warfare. And what is most surprising is that fighting for the Lord is presented almost as a consolation prize for those who aren't able to enlist for the government. (You may be too young to go enlist, but that's OK, you can still fight for God!) I started searching to see if I could find the origin of the song.

The general idea of fighting for God comes from the Bible in 2 Timothy 2:3 (Thou therefore endure hardness, as a good soldier of Jesus Christ) and it has been commonly used by Christians throughout history. One example from 1896 is when a boy, who was visiting the military camp where his father was serving, was asked, "Well my little man, what army do you belong to?" To which the boy replied, "I belong to the army of the Lord, but my papa is only in the district militia." 1

The earliest concrete reference to the song I could find was in a newspaper article from Bangor, Maine dated June 1943 2, which talked about how the song would be used in the closing program for a vacation Bible school on the theme "God's Commandos." It is reasonable to assume that the song gained it's popularity during this time because as children had to watch their fathers and older brothers go overseas to fight in a physical war, they could still play their part by fighting in a spiritual war.

In her autobiography about growing up during the war, M. J. Macpherson said that she remembered singing this song with slightly different words than we know today. Instead of the general phrase "zoom o'er the enemy," it specifically mentioned America's enemy at the time and said "fly o'er Germany." 3Macpherson isn't exact with dates in her book, but her memory probably took place in 1941–42. When the song was first published in a song book in 1947, it used "the enemy." Interestingly, in many post-WW2 contexts the song has been sung "Germany," even though we wouldn't consider Germany still an enemy. 4

That the song would become popular during the war was no surprise, but what surprised me is that it came out of nowhere and no one was given credit for writing it. I kept throwing different variations of the lines of the song into searches on Google, Archive.org, and Newspapers.com, but I couldn't find anything before the aforementioned article from 1943. Finally I got a hit on "never fly o'er Germany." But it wasn't about the Lord's army at all—it was about the actual army.

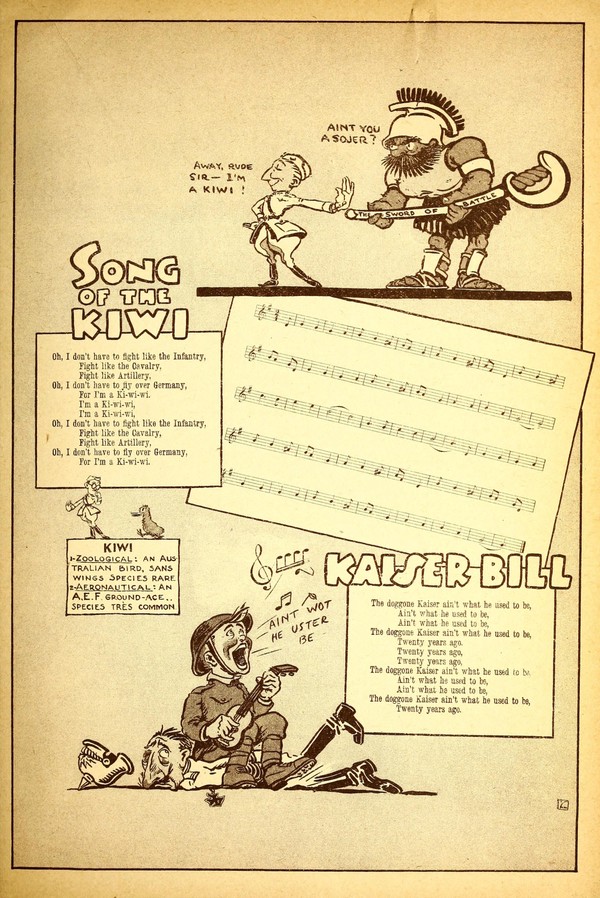

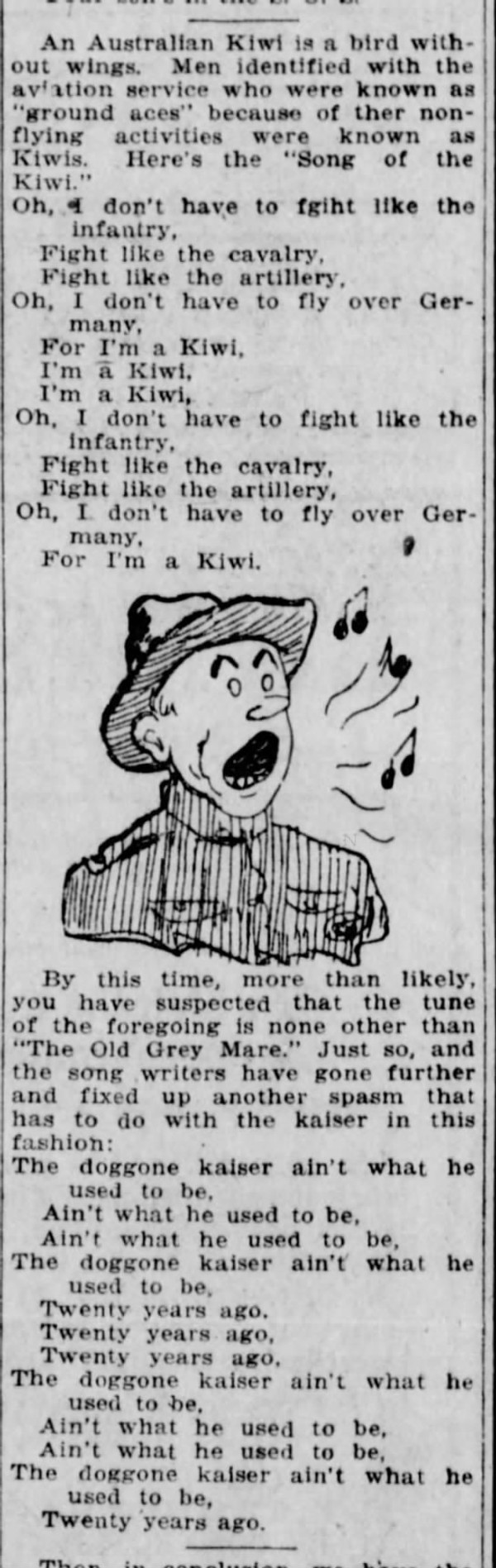

There are many variations of the song that were sung by branches of the allied armed forces. The song was a parody song sung to the tune of The Old Gray Mare (the same tune used by Sunday school children today). The groups that adapted the song were officers that didn't have to fight in the traditional sense like the infantry, cavalry, and artillery had to fight. Those that adopted the song included the King's Navy, Kiwis (ground workers in the air force) , and the Quartermaster's Corp (those charged with securing supplies) 5. I haven't been able to determine which of these variations came first, but most of them came into being during the first world war.

There were also other Christian variations of the song, such as one sung by the YMCA during WWI: 6

Uncle Sammy, he's got the artillery, He's got the cavalry, He's got the infantry, But when, by God, we all get to Germany, God help Kaiser Bill.

And this version sung at an antiwar gala in America in 1938:

We don't want to march in the infantry, Ride in the cavalry, Shoot in artillery, We don't want to fly over Germany, Building for peace are.

So the version of the song that we know today wasn't really original, but it was just the one that remained popular. The discovery of the origin of this song answers my questions about why the song doesn't seem very Christian—because it wasn't one to begin with.